From afar, the fields of concrete may feel cold, but on the inside it’s still hot.

Early last month the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service announced $1 billion in funding to plant and maintain trees in urban communities. The high building and pavement density in these areas contributes to a major temperature increase coined the “urban heat island effect”. City streets can be up to three degrees warmer on average during the day and seven at night.

The Biden Administration adopted 385 spending proposals shot up from organizations around the country working to provide urban neighborhoods equitable access to green space and forestry. It’s all part of President Biden’s initiative to cut the number of people without access to parks or nature in half in the coming decade. These grants will cover roughly 85% of Americans from all fifty states, the District of Columbia, and several U.S. territories.

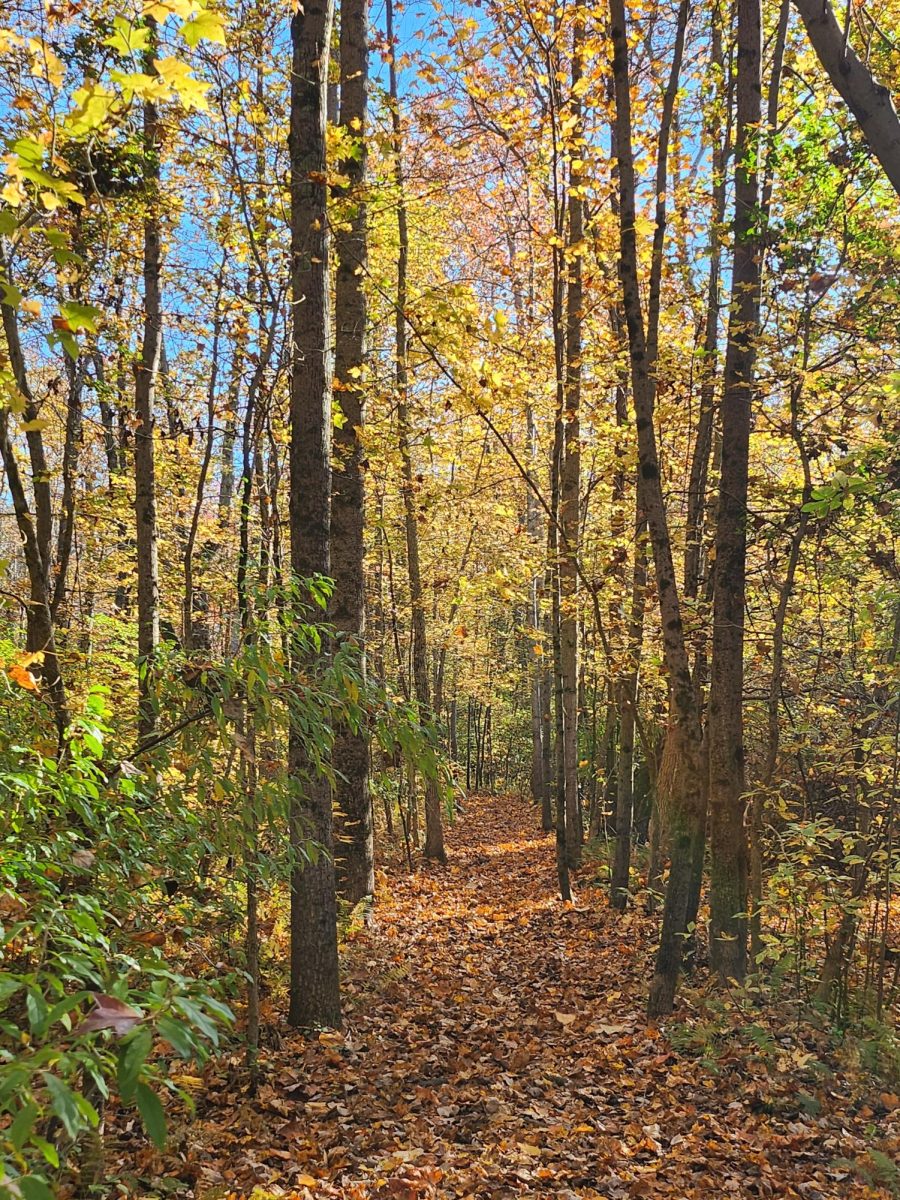

The trees serve much more than an aesthetic purpose, though there’s nothing wrong with a little beautification. The vegetation will lower the surface and air temperatures around the city by increasing shade coverage and through a process called evapotranspiration. At peak temperatures, shaded areas can be 20-45 degrees Fahrenheit cooler than their basking counterparts.

In addition, studies show that increased urban forestry shares a strong association with heightened physical and mental health, boosted economic opportunities, and increased food security. Department of Agriculture secretary, Tom Vilsack, thanked President Biden’s “Investing in America” agenda, saying:

“We are supporting communities in becoming more resilient to climate change and combating extreme heat with the cooling effect of increased urban tree canopy, while also supporting employment opportunities and professional training that will strengthen local economies.”

But some people don’t like trees.

In the case of Buffalo, New York, head of the Parks and Recreation Department, Andrew Rabb, says in an interview with the National Public Radio:

“Oh, they just drop branches. Or they’re growing into my house. Or they just are in the way for me to park my car or something like that.”

Rabb instead plans on redirecting most of the funding towards public awareness of urban forestry and the benefits of a tree-lined street. The remaining will be used to establish a hotline for the people of Buffalo who do want trees, to request one be planted in front of their home.

Whether the hundreds of communities across the country chose to plant their new green right into the ground, or use it to to re-educate their population, the step they choose to take is one in the right direction. The climate crisis will not resolve itself overnight, but a commitment to addressing these types of issues as they arise is the best resistance against the toughest adversary the world has ever met.